We like to say that our coffee isn’t a commodity, and that neither is your team. But what do we mean by that? It comes down to coffee largely falling into two groups: speciality and commodity. On one side you have Pact Coffee: coffees that score 80 or more out of 100 in cupping tests (where experts smell and taste coffee to evaluate its quality), made from beans that are incredibly low on defects and tend to be comprised of a single variety. On the other, you have popular coffee chains: their coffee is made from damaged, defect-ridden and differently sized beans and are often are blends of different origins as well.

Aside from differences in quality, cost (and the way cost is calculated) varies massively between the two types of crop. While speciality coffee is typically sold through various channels including, in our case, Direct Trade, commodity coffee is traded on the stock market - specifically the “[New York Board of Trade [NYBOT], the Kansai Commodities Exchange [in Osaka, Japan], the Singapore Commodities Exchange [SICOM] and Euronext [London]](https://coffeekind.com/blogs/the-reading-room/coffee-and-the-market-an-overview)”. As in, it’s literally traded as a commodity. And that has widespread ramifications.

What goes up, must come down… and vice versa

The trouble with trading something like coffee as a commodity is that there’s a lot of things that can cause prices to fluctuate. And those things range from the physical to the imaginary. Unexpected inclement weather is one, destroying coffee crops and resulting in a mad dash to trade… though a dry season can also have the opposite effect, where bountiful production means prices crash.

But it’s more than just real-life events that affect what price coffee is trading at. Trade speculation also plays a part - anticipated crop shortages prompt some people to “hedge buy coffee contracts”, in order to sell at a profit later. And that results in an ‘imaginary shortage’, putting prices up even further. And, again, the opposite can happen when hedge funds are short-sold (which means traders borrow shares and quickly sell them again, hoping that they can re-buy and return to the lender later - pocketing the difference). This can drastically reduce prices, meaning farmers can even make a loss.

Crashing prices, worthless crops

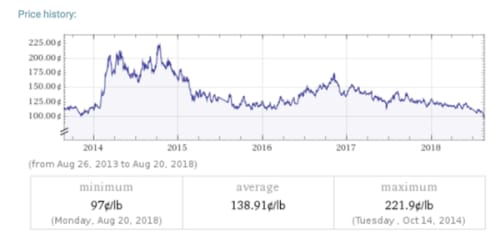

A drastic drop in coffee prices is happening right now. Arabica coffee has slid to below a dollar per pound ($0.99/lb, as of the 20th August 2018) - and this is an astonishing thirteen-year low. It might be difficult to really understand how cheap that is, but consider who gets a slice of that especially small pie. Our Head of Coffee estimates that commodity coffee producers (excluding those in Brazil, due to their highly efficient production rates) have costs of $1.50 per pound. With the market hovering around $1, and the other coffee companies involved in the supply chain taking two thirds of the profit, the farmer will be paying to sell their coffee. They’re losing money with each sale.

But why have coffee prices fallen this time? In this case, it came down to some coffee farmers doing very well - Brazil’s projected crop production is much higher than expected. And a larger amount of coffee being on the market than expected means the overall cost of commodity coffee is devalued. So a successful crop can lead to a not-so-successful season financially.

What complicates matters is that when coffee prices fall, it triggers a very specific cycle. A perfect example of this can be seen by looking back to 2013:

Prices crashed to a similarly low level of around $1, which meant it was ‘buy buy buy!’ when it came to coffee. But coffee was suddenly became in very short supply, for several reasons. Not only was there just less coffee to go around, as it’s all being bought up, but farmers stop producing during a crash like this as it’s just not worth the time, energy or cost - “some go so far as to uproot or burn down their coffee trees in order to plant a more profitable crop”.

Speciality coffee: a saving grace?

Coffee farmers are, by and large, the biggest victims of this unstable market. With no choice but to accept prices that don’t even cover their costs, smaller farms are particularly at risk of folding. “Why bother growing commodity coffee, then?”, you might wonder. The problem is that small farms don’t have the resources needed in the first place to go beyond commodity crops, meaning they are tied into a shaky global market - for better or, more often than not, for worse.

But say they _could _cut free from the crashing prices and catastrophic losses that come with commodity coffee. What’s the benefit of producing speciality crops? Following the old adage of ‘you get what you pay for’, speciality beans are more expensive (to produce and to buy) and of a better quality. They’re subject to rigorous controls, by organisations likes the Speciality Coffee Association:

In order to be considered “speciality coffee,” a sample of a specific size must have no primary defects and no more than five secondary defects. And by “no more than five defects,” the CQI means no more than five defective beans, even if they all display the same defect.

Defects show more than just a problem in bean quality, but also betray the mistakes made by growers and sorters throughout processing. Speciality coffee is not just good coffee, it’s also a crop that has been shown a lot of care and attention.

It goes without saying that people will pay more for better quality coffee. But it’s also undeniable that, not only do speciality coffees cost more to produce, they’re also not immune to what’s going on in the world of commodity. If commodity prices are higher, then speciality prices will be forced up too - because, in the case of Fair Trade coffee, they used commodity market prices as a base price to exceed. Our aim is to make speciality coffee make sense for farmers.

The impact of Pact

There’s two things Pact does to make speciality coffee worth farming. We make it a realistic option for farmers, and we pay a price that isn’t influenced by the commodity market. Fair Trade only acts as a ‘safety net’, not paying more when market prices are at or exceeding an ‘acceptable level’, but just making sure farmers break even when prices fall. But Pact is committed to Direct Trade. Working directly with coffee farmers means we can pay a lot more than Fair Trade prices to start off with, so they make a profit on top of their costs being covered.

As we’ve seen, however, the major obstacle is being able to produce speciality coffee in the first place - in terms of having the time, resources and funds. And that’s where Pact comes in, again. Our Three Phase Programme allows us to find farms that have the raw potential to produce a speciality crop. That’s the first phase: finding them and getting them to produce a sample of the best coffee that they possibly can. From that, we give them guidance and suggestions to push this further.

The second phase involves making small technical investments, allowing them to purchase the correct tools and processing equipment to produce a quality small-scale batch of speciality coffee. And the third phase? Scale up! We work with local agronomists and the farmer to find the best way for this coffee to flourish, taking into account the local environment and other factors. This lets them make more speciality coffee which we can buy and bring home for you, our Pact customers!

Take-away cup

For many people involved in the coffee industry, it’s a volatile and uncertain way of life. Anything from heavy rainfall to the vaguest suggestion that there may, at some point, be heavy rainfall can hugely affect the livelihood of millions of farmers. The trading of commodity coffee leaves farmers paying to sell their own crop, doing back-breaking work for the sake of losing money, and for what?

Pact Coffee is always speciality grade and sourced using Direct Trade for a reason. As we like to say, it’s about quality - not charity. We help coffee farmers become experts in their field, in their communities, in the world. And while that benefits them, by giving them a secure and profitable livelihood, it also benefits us. We get world-class coffee in return, coffees that score incredibly high and have been hand-reared to produce a cup that knocks everything you’ve ever tasted out of the water. It’s mutually beneficial and, more importantly, it’s sustainable. We’re pretty proud of ourselves and if you or your office want to join us in making coffee a force for good, you can be too.

Views: